Summary

This page provides an advanced analysis of technology that addresses: a) its fundamental nature, b) its relationship with knowledge, and c) its role in education.

Contact Information

Trace Mansfield

tmansfield@lesd.k12.or.us

Introduction

This advanced analysis addresses the fundamental nature of technology, its relationship with knowledge, and the consequent role of technology and Assistive Technology (AT) in education.

AT is often treated as if “technology” were just the application of specific tools (e.g., switches, interactive whiteboards, pencil grips, eyeglasses, and so on). Sometimes, that perspective is sufficient to bridge an immediate access gap: you see a nail, you buy a hammer. Sometimes that acts like enough.

But technology is fundamentally not a set of objects in the outside world. While a number of theoretical approaches would tend to disagree, they are simply wrong, and all for very similar reasons that are pretty easy to explain and remedy. Making this correction is worth the effort because it affects the quality of service that we provide.

This training, then, is intended for those people who do not want to be limited by a bag of hammers; in other words, you can be ignorant of the Maillard reaction and still know how to brown foods… until you need to invent a tool that will do so effectively in a microwave, which requires knowing why foods brown. So let’s talk about what technology really is, and why it works.

Jectivity

From your perspective, you are the only subject. You, as a subject, exist as your thoughts, feelings, beliefs, sensations, perceptions, awareness, sense of self, cognition, and so on. Your subjectivity is the interaction of all of those internal, “mental” entities. And while you can entertain the notion that other people feel the same way about their own status as a subject, ultimately you can only take their word for it.

Everything other than your subjectivity is an object.

Your array of sensory organs and perceptual processes act as the gateway between you, as a subject, and the external world of objects.

If you treat something as part of your self, then you are subjectivizing it; for example, if you think that the world is dark because you have forgotten that you are wearing sunglasses, then you have subjectivized that eyewear. They are now a subjective part of your view of reality. They are not “on stage” for observation.

In contrast, if you treat something as not being part of your self, then you have made it an object of observation; for example, if you spend time analyzing your feelings, then you are objectivizing them. You have put them on stage as objects.

This is not something that gets talked about very often in typical conversation, so it tends to get referred to rather clumsily as “subjectivity and objectivity.” We will just use the term “jectivity” to emphasize the spectral nature of those states; that is to say, despite the rather strict definitions that we have given above (for purposes of a clear introduction), an entity doesn’t need to be absolutely subjective or objective.

Technology allows us to adjust the jectivity of a person’s reality. We want any AT object/tool (e.g., wheelchair, AAC system, pencil, and so on) to become increasingly subjective for the user. We want it to become a window of opportunity.

Having established this common vocabulary, let’s extend your exposure to the related theories that deal with technology and education.

Technology is an Emergent Property

Karl Popper suggested a three-world model of reality:

- World 1: the physical world (of which we all share an objective experience)

- World 2: the non-physical world (which each individual experiences subjectively)

- World 3: the products of thought about World 1

In Popper’s view, those products can be internal (e.g., the idea of a microwave browning dish) or external (e.g., an actual dish). World 3, then, is portrayed as an emergent property of Worlds 1 and 2, much in the same way as the color green is a property emerging from the interaction between blue and yellow pigments, or language is a higher-order cognitive function that emerged from lower-order nature and nurture functions (i.e., there is no autonomous “language module” unique to the development of human cognition).

Beretier (2002) cast Popper onto education, as explained concisely in Hattie (2008), digested for simplicity as follows:

- First world: physical reality (object, facts, surface knowledge)

- Second world: non-physical experience of reality (subject, thought strategies, deeper understanding)

- Third world: constructed models of reality (subject’s objects, products of thought, cognitive models of reality)

Some learning, then, is commonly represented in terms of first- and second-world understanding (i.e., surface and deep knowledge), which obscures Popper’s distinction between the physical and non-physical domains. A person then emergently builds their third world out of the first two; that is to say, they create their individual subjective model of our shared objective reality. Crucially, that cognitive model is populated by real entities; for example, you achieve your best understanding of a paper airplane when you can {un/re}fold it cognitively, rather than having to manipulate it physically to predict what will happen. That cognitive model is a real thing. It could be a mental picture, a set of propositions, a description in so many words… it will vary depending on the person. Whatever it is, it is associated with a real process of neurochemical events.

This third world, then, is what Hattie identifies as “the major legacy of teaching.”

Let’s start with an example. It is a good idea to use math manipulatives, such as a balance and weights, to demonstrate addition and subtraction. In the first world, the students learn to use the scale. In the second, they learn to associate the behavior of that scale more deeply with the mathematical functions that it models. In the third world, the student has created a cognitive model of that balance that they can use instead of the physical scale. When that happens, they have moved beyond simply knowing how to and closer to understanding why.

Put in more abstract terms, you want to learn something so well that you can model it cognitively, and do so with enough precision (compared to objective reality) that you can accurately anticipate the objective results without always having to experience them first in the physical world; similarly, you want to teach well enough that your students can get to that place in their understanding as well.

You want these models (of tools) to become so subjectified that your students are able to rely on them without having to treat them as objects.

A hammer, then, is not really the ‘T’ in ‘AT’. Neither is an iPad. Nor is fire. Instead, technology is your understanding fire so well that you can accurately model its use and its consequences before you actualize any given instance of fire in objective reality. Technology is your model of fire, your understanding of what fire is and what it does. Technology, therefore, emerges from the interaction between subjectivity (your sense of self) and objectivity (your sense of the world outside of yourself). Technology is your third world, your ability to create and use such constructs, which adapts to your creation and use of strategies and tools in objective reality.

This model aligns consistently with our advanced training on Communication Disorders Therapy for intensely special education. For access to that tutorial, get in touch with the contact listed in the Quick Links.

AT is a Vehicle

Our definition of technology is not just a semantic game. You extend your sense of self into a physical tool as you use it (expanding your peripersonal space (link opens in new tab/window)), such as when you are:

- driving a vehicle;

- playing a musical instrument;

- swinging a bat;

- wearing glasses, a costume, or VR gear; or

- dancing with somebody.

The more that you get used to a system being a subjective part of you, the more it feels like a natural, unaided part of you, and the easier it is for you to blend back into it every subsequent time that you go to use it.

So one important part of all of this theoretical exploration is:

AT systems are vehicles with which a user navigates equitable access. The user extends into the AT system; that is to say, every AT system is similar to an exosuit in that way.

While you do not need to understand this sort of involved material to know when to buy a kid a fidget, learning about it can potentially help you to do more than just buy fidget after fidget after fidget for the rest of the student’s academic career.

And yes, this does become much more challenging when the student’s sense of self is not conventional, which is why we also provide the CDT training mentioned above.

AAC is a Vehicle

This perspective can also help you to undertand the nature of such sophisticated AT as an AAC system. The AAC user is extending their personal model of reality through the linguistic structure embodied by that system, so its design and maintenance should merit some care by a well-trained individual; in other words, when you change a system, you are changing a person.

Now you are better prepared for an accurate understanding of the TPACK model.

The TPACK Model

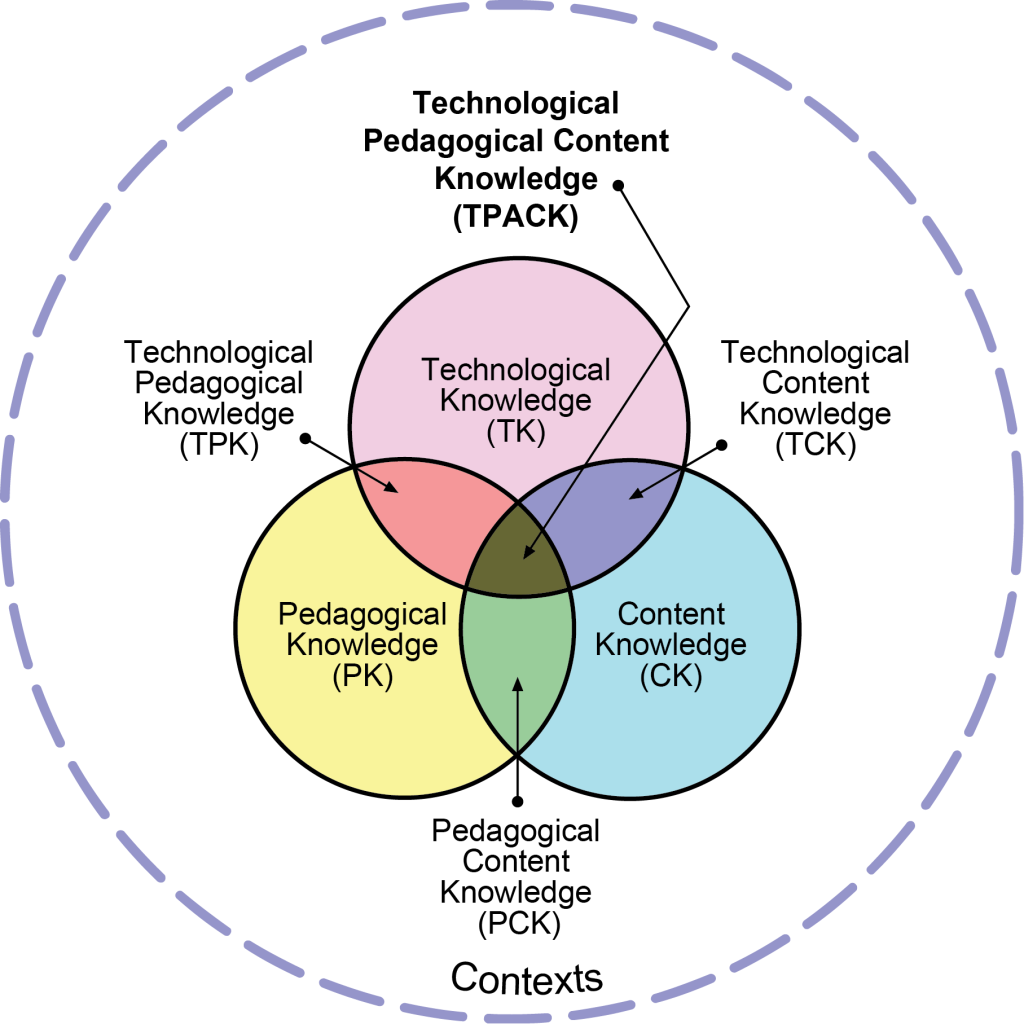

Sooner or later, people who work in the field of AT end up coming across the TPACK model. It is designed to help people understand the role of technology in education, but we have heard it misinterpreted often enough that we will address it here.

The TPACK diagram looks like this, with each circle representing a second world (i.e., the teacher’s relatively deep knowledge regarding a topic):

- Content = the topic that they are teaching

- Pedagogy = teaching itself as a topic (about which to gain expertise)

- Technology = technology as a topic (not comfort with various classroom tools)

Reproduced by permission of the publisher, © 2012 by tpack.org

At base, the TPACK model says that a teacher should learn just as deeply about technology as they do about pedagogy and their content area. They need to go beyond just learning how to use specific classroom tools.

Which is the very reason that we are fostering that deeper understanding of technology with this discussion.

But why is that depth of technological knowledge important?

Because your (subjective) second-world understanding will interact with objective reality, and then your third-world cognitive models (i.e., your constructs) will emerge. The “vehicle” or “exosuit” model of AT is just such a construct, one that helps you to internalize an understanding of why a change in a system can change its user.

This is how the ‘T’ in ‘AT’ applies to education.

And now for the application of the ‘A’.

Independence

Crucially, the TPACK diagram is just a 2D slice through a 3D object; that is to say, each circle is a cross-section through a cylinder (or maybe a spindle), and the whole thing is skewered down the center by at least one additional dimension, namely a measure of “(in)equitable (in)dependence.” Imagine that any given circle, then, is a slice through a cucumber, and that the line of seeds through the cucumber is that dimension of (in)equitable (in)dependence.

Dependence is not binary; that is to say, it is not a matter of simply being wholly dependent, or wholly independent. And there are not only degrees of dependence, but kinds of dependence (e.g., wanted vs needed, acute vs chronic, habilitative vs rehabilitative, and so on). There is an area within the notion of dependence that describes improving equitable access to functional capabilities. And that’s the ‘A’.

With that in mind, step into the third world of constructs and imagine a braid made of strands of many different colors, or, as in the TPACK diagram, just three colors that blend where they touch. (It might just as easily be different textures, and so on, rather than specifically a visible sensation like color.) Now, search along that braid until you find the “assistive” area (as opposed to the “independent” area, and so on), slice through that part, and the end should seem something like the TPACK diagram.

And that’s AT.

Which, as you recall, overlaps with CDT at AAC.

Autonomy

Beyond independence, autonomy is rightful access to choice, or self-directed decision making. Scaffolding autonomy is crucial for promoting the development of self-determination. The following work provides an exceptional explanation:

Galaxy, Annie (2024) Empathic Education: Perceptions of Self-Determination by Rightful Presence. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon]