Summary

This page describes the sensory lifestyle components that support experiential variety in the Life Skills classrooms, which is crucial for communication and language development.

Contact Information

Trace Mansfield

tmansfield@lesd.k12.or.us

Introduction

When a person’s engagement with their environment is limited (perhaps due to sensory or mobility challenges), Assistive Technology can help to make that access more equitable.

While there is certainly value in improving a person’s sensorimotor experiences across a set of daily activities, ultimately we are scaffolding the development of functional, effective communication.

Without resorting to the advanced tutorial that is linked above, it is not possible to provide a truly adequate explanation for why this is so; however, a few illustrative examples might help:

- No mere explanation of an orange can do it full justice; therefore, if only some of the participants in a conversation have actually experienced an orange, then the word “orange” will not have the same meaning for all of them. (If that example doesn’t move you, substitute a food that you categorize as more exotic, such as Guaraná Antarctica, fried spider, baklava, or balut.) And of course, some people do not take food orally.

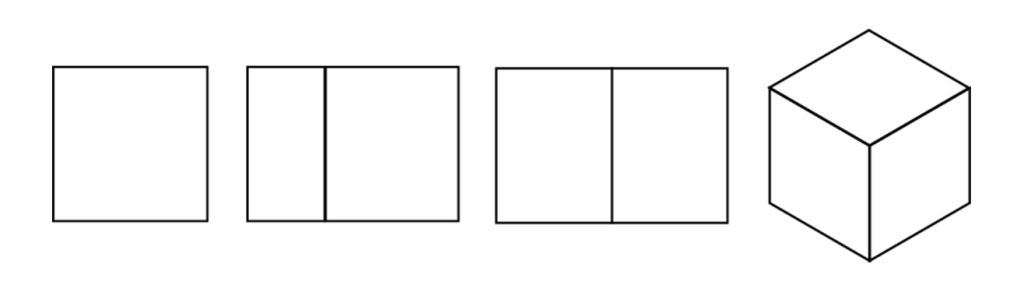

- When the person’s manipulative abilities are limited, perhaps along with mobility in general, then so is their physical interaction with their environment, and that can impact their understanding of the world; for example, when a person physically manipulates items, they also learn how objects behave when they are moving elsewhere in their visual field. It might take those people much longer to learn that with rotation, any of the following shapes might turn out to be a cube:

- Many people only get to touch items that are brought to them by someone else, and a sensory limitation will affect a person’s experience of their environment even if items are brought to them.

All of these experiences contribute to the individual cognitive model that a person makes of the world that we all share. A person whose experience is intensely diverse will necessarily create an equally divergent model, making it that much more difficult to communicate with their partners. Imagine if you were not just the only person in your social group who had never eaten an orange (when all they wanted to talk about was oranges), but in fact you were the only person who had never had much sensory or physical experience of the world at all (when all that your group wanted to talk about was that world).

So an enriched sensory lifestyle (formerly called a “diet”) is not simply valuable as a matter of supporting experiential variety for all of our students, but is crucial for communication development.

The following sections talk about things to consider when: a) implementing or designing (with a specialist) a sensory lifestyle; b) engaging in straightforward sensory interactions with students (including adjusting their environment); or c) just trying to figure out what’s going on in a student.

All of these activities can involve simple passive sense experience (with the cautions given below), or you can work up to such activities as item identification.

Olfaction (Smell) and Gustation (Taste)

Sense and taste are usually integrated as olfaction, but when you have atypical cognition, they can be poorly coordinated. Then of course we have students who have very limited experience with taste due to feeding/swallowing restrictions. (Make sure that you check with the classroom SLP about the student’s feeding/swallowing protocol before experimenting with tastes. And watch out for allergies.)

Remember: gloves are not for your protection alone; you wear them to protect the student. If you put on gloves and then touch your cell phone, or the table, or anything else, and then use that gloved hand to put food in a student’s mouth, then you are putting them at risk. Don’t touch anything with that gloved hand that you wouldn’t put in their mouth.

Some students are very sensitive to the smells of volatile materials that we tend to filter out, such as glue, paint, restrooms, markers, and so on. And, seriously, do not apply ancillary scents to yourself when you are going to be working in the classrooms.

Scent kits are useful (e.g., small containers of scented, colored wax), especially when you have one that relies on conventional scent/color association (e.g., purple-grape), and one that contains more unusual scents. Scented crayon sets are a fairly good alternative.

Vision (Sight)

Include a range of visual materials/reinforcers into your classroom environment for your students in general. Any student facing vision challenges strong enough to qualify for VI services will be assigned a Teacher for the Visually Impaired (TVI) who will provide equipment and services (i.e., they are also a primary person whom you would ask for help). Tactile schedules are discussed under Taction.

You will hear about Cortical Visual Impairment (CVI), which tends to mean (give/take) that a student’s eyes function, but there are problems with the brain areas that would otherwise tend to process the information coming in from the eyes. Earlier, we discussed the myth of the Swiss cheese metaphor. There are a couple of things that you should know:

- Cortical impairments can affect the processing of the information coming in from any or all of the senses.

- Do not demand eye contact (or other sensory focus) as a sign of attention/attentiveness. Some students have difficulty marshalling their limited resources, and asking them to spend effort on eye contact can reduce the energy that they can spend on anything else, like thinking.

This is common sense, but it is still worth saying: have things within the student’s reach.

The following are the sorts of skills that might be pursued by a student with vision challenges. You can start by introducing and explaining the skill with a sensory modality that is clearer for the student, such as holding off on visual discrimination until after the student has practice with discriminating important sounds (i.e., signals) from irrelevant ones (i.e., noise). The notion is to help the student learn what you want them to do before they have to spend resources on the vision challenge:

- discrimination of colors, patterns, and other salient features of visual images,

- localization (identifying where something is using one’s senses),

- direction (up/down, left/right, and so on),

- visual scanning (follow a sequence of visual cues to navigate a task),

- direction of gaze fixation/tracking, and then focus gaze to track something as it moves through the environment (or to follow an outline or row of text),

- using visual information to help with a subsequent touch task (e.g., seeing that an item is fuzzy can help to identify it by touch), and

- associate the visual perception of a form with a meaning.

The TVI can provide expertise in a sensory lifestyle design that draws on actual developmental scope and sequence.

At base, though, you have to exercise some care in the choice of representations that you are using with a student (i.e., pictures, audio cues, tactile object sets); for example, if you are using pictures, will they be:

- Realistic ←→ Abstract (e.g., photos, cartoons, line drawings, sight words)

- Color, monochrome, greyscale, black and white

- How many in a field (from which to choose)?

- Contextual (i.e., a figure with a background)

- Multimodal (pictures with audio feedback, pictures with raised textures, and so on)

For pictures, there is a test that the AAC Specialist can administer that can help to figure this out (Test of Aided Communication Symbol Performance; TASP).

Audition (Hearing)

Every Life Skills classroom is equipped with at least two sets of headphones that allow for mono/stereo selection, with separate volume controls on each earpiece. There is also at least one set of noise reduction headphones (and usually more).

Noise can be:

- stressful at the level of a noisy restaurant,

- damaging at the level of a school cafeteria (with prolonged exposure), and

- painful at the level of a siren.

For example…

| Example of Sound | dB | Distance | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| near total silence, beginning of hearing | 0 | ||

| mosquito | 0 | 3 m | |

| leaves rustling in the trees | 10 | ||

| pin drop (1 cm fall) | 15 | 1 m | |

| whisper | 15-30 | ||

| watch ticking | 20 | near ear | |

| quiet conversation | 30 | ||

| refrigerator (condensor running) | 40 | ||

| spoken voice, washing machine, quiet radio, normal home, light traffic | 50 | 30 m | |

| normal conversation | 60-70 | 1-2 m | |

| air conditioning unit | 7 m | ||

| sewing machine, normal street traffic, normal piano practice, dishwasher | |||

| busy traffic | 70 | 1 m | Disruptive, stressful (with prolonged exposure) |

| noisy restaurant, TV, bathroom fan | |||

| heavy city traffic | 80-85 | 7 m | Must raise your voice to be heard. Continued exposure leads to hearing loss |

| school cafeteria, vacuum cleaner, garbage disposal | |||

| lawnmower | 90 | Hearing loss exposure: 8 hours | |

| jackhammer | 95 | 15 m | Hearing loss exposure: 4 hours |

| motorcycle, snowmobile | 100 | Hearing loss exposure: 2 hours | |

| personal stereo (iPod) at maximum level | 105 | Hearing loss exposure: 1 hour | |

| car horn | 110 | 5 m | Hearing loss exposure: 0.50 hour |

| sand blasting, rock concert, or orchestra | |||

| drum kit (continuous average) | 115 | Hearing loss exposure: 0.25 hour | |

| rock concert (in front of speakers) | 120 | Hearing loss exposure: generally within a few minutes. Pain starts here. | |

| thunderclap overhead, jet engine or siren | |||

| diesel engine room, drum set at moment of strike | 125 | ||

| gunshot, firecracker, jet engine | 140 | 30 m | |

| jet taking off | 60 m | ||

| toy balloon popping (dep. type and distance), professional fireworks | 150 | ||

| firecracker or shotgun firing | 165 | close | Hearing loss exposure: immediate |

| rocket launching pad | 180 | Death of hearing tissue | |

| 1000 kg of TNT | 195+ | 20 m | Death from shockwave alone |

For some of our students, noise can be stressful and painful at much lower levels than you might expect, where even a room that is full of typical conversation can cause distress. If you have to raise your voice to be heard above the noise, then continuous exposure at those levels can cause hearing loss, and that environment is likely to be stressful and possibly painful to some of our students.

Fluorescent lighting is not easy to pin down in terms of decibels. It’s the transformer or “ballast” that makes the noise. It is usually around 20 dB, but it’s also typically less noisy because it’s at a distance of 2-3 meters away. We can usually only hear differences in the 3 dB range, so it will tend to be drowned out in a classroom with normal noise levels. In other words, this buzz can be more disturbing in a particularly quiet room. Instead of going for pure quiet, you might try this:

- White/Pink/Brown noise: fan, aquarium pump, air purifier, radio static, and noise-generating software

Of course, some students find white/pink/brown noise more irritating than “regular” noise.

Any student facing hearing challenges strong enough to qualify with a hearing impairment will be assigned a Teacher for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing (TDHH) who will provide equipment and services, such as a personal FM system (i.e., they are also a primary person whom you would ask for help).

Taction (Touch)

Cautions:

- In some cases you will want to consult with other specialists, including the student’s doctor, before introducing therapy that involves touch; for example, you would not want to introduce a spine-massaging chair pad if the student has just had spine fusion surgery.

- Do not use food as a manipulable. There’s the waste, the mess caused by sugar, confusion with food differentiation and desensitizing, and so on. Food/Eating programs have value in a sensory curriculum, but can be very involved and should be approached separately.

- Some small manipulables are choking hazards.

- Some materials can cause allergic reactions (e.g., fur, latex gloves or balloons, and so on).

- If the student is challenged with tactile defensiveness (i.e., protective responses to touch that drown out discrimination functions), then you will want to consult first with someone who is trained in treating sensory integration dysfunctions (often an OT for touch in the main, or an Autism Specialist, and some SLPs and AT folks).

- Stretchy items, such as TheraBand, tend to have their own cautionary documents (so that folks don’t get snapped, and so on).

A sensory lifestyle can usefully include exposure to different textures, physical states, and so on (supplied by various specialists). You might try the likes of:

- Dry particles (beans, sand, pellets, marbles, ball bearings, packing peanuts, rice, dirt), use with or without things buried in it to find

- Dry or wet cornstarch

- Liquid (water, soap, paint, gel, foam, silt/slip) as above (different temperatures)

- Dry or wet clay, putty, dough, mud, cornstarch balloon, grip strengthener

- Hard stuff: metal, glass, plastic

- Sheets (rubber, paper, newsprint, fur, sandpaper, foil, wax paper, metal sheet from foil on up, plastic sheets from clingwrap on up, see Fabric)

- Fabric: gauze, canvas, silk, satin, lycra, aida cloth, felt, velvet, velour, vinyl, denim, flannel, corduroy, angora, tapestry, burlap, chamois, crepe, embroidered fabrics

- Strings: rope, string, yarn, beaded necklace, chain, cord, shoelace, thread, hair

- Rubber balls of various firmness and texture: Koosh™, bumpy ball

- Blocks and stuff that go together with a click, snap, release, or whatever

- Simple geometric objects: book, ball, tongue depressor, pencil/pen/crayon

- Complex geometric objects: teether, toothbrush, hairbrush, pillow, vibrators

The following types of activities involve significant amounts of touch feedback:

- Dress up (but exercise some reasonable caution around hygiene, like not sharing wigs)

- Gardening (tool use, soil textures, weather)

- Scrapbook (cut/paste, press, glue, turn page)

- Swimming

- Blowing bubbles

You can practice touch in itself, but also consider such variations as touch firmness/intensity, frequency, duration, and the like.

You can also engage in activities where something touches them:

- Massage (note that some touch, even light touch, can be irritating)

- Between pillows

- Swaddle

- Roller, ball over skin

- Squeeze machine

- Press palms together.

- Pull on each finger.

- Brush with materials listed above.

A sophisticated touch activity involves the development of a Tactile Schedule (coordinated, at the very least, with the classroom SLP).

Tactile Schedule Practice

We can associate the feel of an object with the sound of a word to reinforce its meaning. It can be useful to give a student as richer sensory image (i.e., include visual and tactile input) when their auditory processing is too challenged to be sufficient on its own.

This is an example of an introductory, practice tactile schedule:

| Sequence | Object | Means | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On the way | Key | apartment | ||

| On arrival | Block | speech | ||

| In class | 1 | Comb | grooming | |

| 2 | Bell | device | music on | |

| 3 | Marker | art | ||

| 4 | Spoon | eat | several bites | |

| 5 | Sanitizer | wash hands | ||

| 6 | Bell | device | music off | |

| 7 | Comb | grooming | ||

| 8 | Wadded paper | recycle | ||

| or | ||||

| Eraser | classroom | |||

You would use these objects in much the same way as visual prompts; for example, you would consistently hand the student the spoon when it was time to eat. Ideally, the student would learn to communicate some of these meanings by selecting the appropriate item and giving it to a communication partner. If this were to be an actual communication system for a student, the SLP would design it.

Notice that some objects will be fairly concrete, such as the spoon for eating, but others are entirely abstract, such as the block to represent speech therapy. Objects that might seem to be concrete to us, such as a toy bus representing ‘time to get on the bus’, might still be abstract to one of our students.

For students who do not rely on a sophisticated tactile schedule, we still sometimes select a small set of specific helper objects, such as a specific stuffed animal that consistently means ‘go to story time with friends’.

Much like a successful custard, consistency is the key.

Proprioception and Balance

You might hear proprioception (i.e., “one’s own” sense) referred to as “joint feedback,” because there are sensors in your joints (and elsewhere) that help you to get a sense of how your body is positioned in your environment. Crucially, for our students, it is also supposed to give you a sense of what stuff in your environment belongs to your body and what does not. Imagine what it would be like not to know that the thing that you’re looking at is your hand, as opposed to just some thing sitting around. Some of our students can experience a sense of distress over feeling unanchored in space, and do well with the application of “deep pressure.” Talk with the student’s specialists (e.g., OT, PT, Aut/Beh) about their programs for them.

BodySox and weighted/neoprene vests are often worth subjecting to trial, and there are several weights/strengths of TheraBand (which is like a big rubber band) that might be used in consultation with the PT.

You might try a “steamroller” (which is one type of squeeze machine) or a “BOSU ball” (which is a sturdy, inflated hemisphere used for balance and body feedback) which are sometimes available through a Regional library.